A little while ago, I spoke with Annica Hulth from Uppsala University about volcano research in Uppsala. It was a lovely experience to take part in an interview about my research. The piece written by Annica is below.

Volcanoes both fascinate and frighten people because of the beautiful landforms they create and the powerful force of volcanic eruptions. Studies of rock, minerals, and gas erupted from volcanoes enable researchers to look into the earth’s interior and help to provide important information to people who live close to active volcanoes.

Frances Deegan is part of a research team at the Department of Earth Sciences which specialises in volcanoes. She is a geochemist and studies the interaction between magma and limestone in volcanoes in various parts of the world.

She has been, for example, to Merapi in Indonesia and Vesuvius in Italy, which are still active volcanoes in carbonate-rich areas. Some of her work is done in the laboratory where she analyses samples of solidified magma.

“Crystals that grew in magma are fascinating because they can record the history of the volcano including where magma is born, how it is transported to the surface, and what processes it undergoes on the way,” says Frances Deegan.

“I also love to replicate volcanic processes experimentally in the lab and I am interested in how gases released from volcanoes can affect earth’s atmosphere and climate.”

When carbon dioxide bubbles up

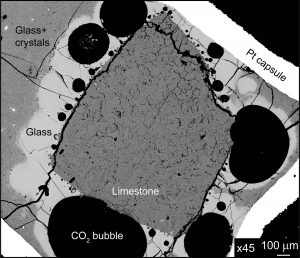

This was the subject of the most recent study, which was carried out in collaboration with Italian and Swedish researchers. The team showed experimentally what happens when carbonate-rich rocks such as limestone and marble come into contact with magma beneath volcanoes.

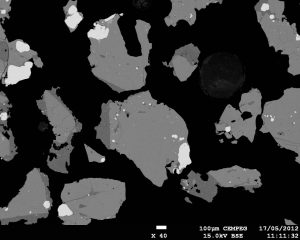

Small capsules containing limestone and crushed lava were put in an oven and subjected to the same intense pressure and temperature as exists underneath volcanoes.

“The results were very bubbly,” says Frances, “just like when you put a sparkling vitamin C tablet into a glass of water.”

The bubbles were CO2 which are generated when magma meets limestone and eventually comes up to the earth’s surface and then out into the atmosphere.

“This is interesting because it can help scientists to learn more about the natural carbon cycle, which is very important especially since humans are currently interacting with such cycles on earth,” says Frances Deegan.

All kinds of volcanoes studied

The research team studies all possible kinds of volcanoes in every part of the world. These might be oceanic islands such as the Canary Islands or Cape Verde, subduction zone volcanoes such as Vesuvius, active volcanoes in Iceland and Indonesia or very old extinct volcanoes such as in the Canadian High Arctic, Ireland and Great Britain. Some of the researchers also study African volcanoes, for example in Cameroon.

An article was released recently about the Icelandic volcano Holuhraun and one of the world’s most closely monitored volcanic eruptions. It was not a violent eruption but it could have gone badly if the magma had taken another route through the bedrock. The eruption started under ice but instead of going straight up – which would have led to a more explosive eruption – the magma went 45 km towards the north-east and came up to the surface at Holuhraun, just beyond the edge of the glacier.

Many live close to volcanoes

In the above case, there was nobody who lived close to the volcano. The eruption, however, did attract many tourists who came to watch. In other parts of the world, it is common to find major cities close to active volcanoes, for example, Naples and the volcano Vesuvius in Italy.

“Research on volcanoes can help the people living nearby to understand them better and hence to be better prepared for an eruption. Volcanoes are extremely hazardous and yet many people live near them – learning about how they work is therefore not only very interesting but it is also necessary,” says Frances Deegan.

The study of volcanoes is built upon international collaboration and is of great help to local researchers who, for example, can record signals from volcanoes using different measuring instruments.

“We can’t predict eruptions, but we can try to be prepared for the type of eruption that may happen. Some volcanoes are very explosive and others not so dangerous. And all volcanoes have different personalities,” says Frances Deegan.

Annica Hulth

A version of this article appeared on UU’s website here and an article about our most recent research into limestone assimilation published in the journal Scientific Reports, can be found by clicking here.